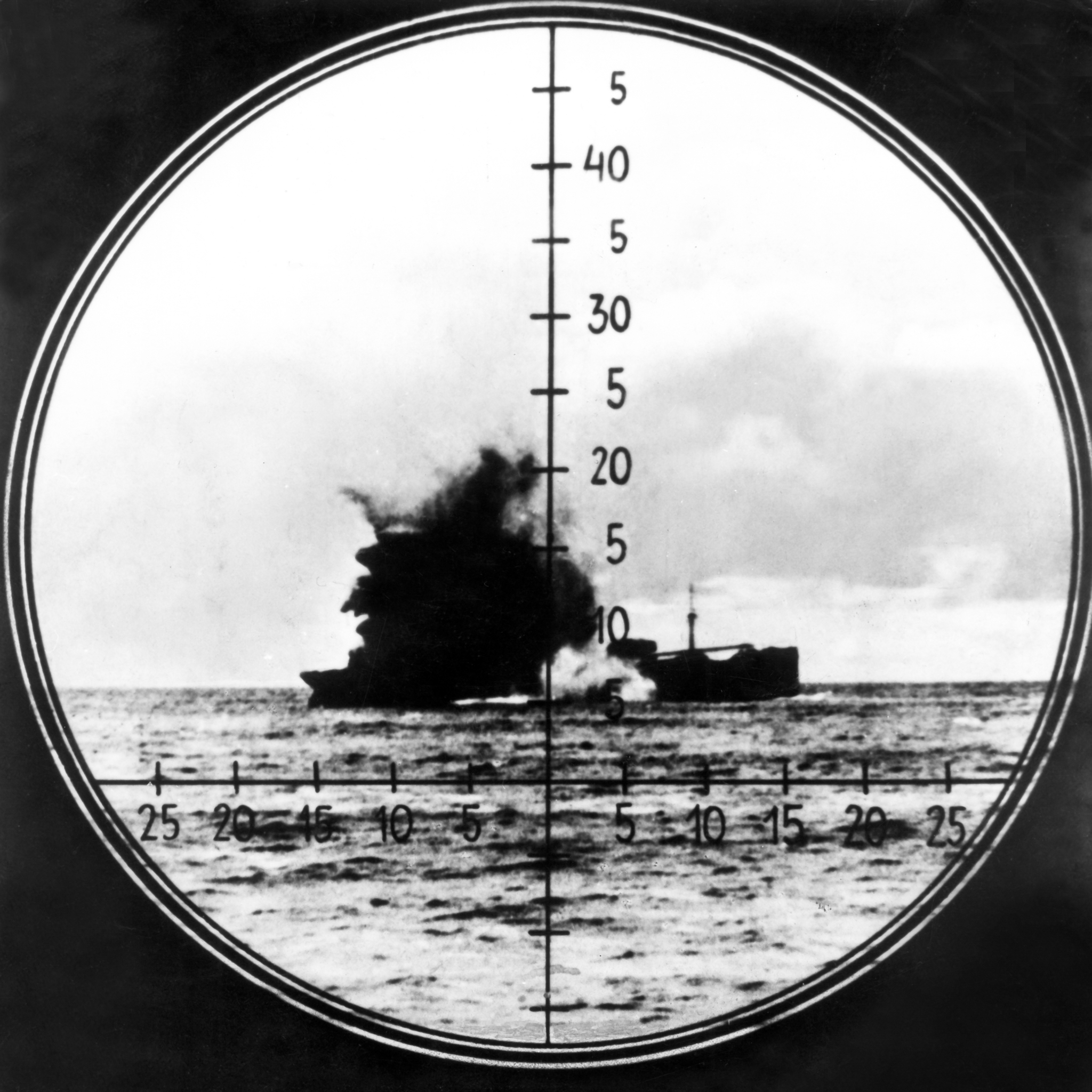

Photograph by ullstein bild, Getty Images

See how Nazi U-boats nearly won WWII in these striking maps

The fate of Europe hung in the balance 80 years ago during one of the fiercest sea battles in modern history: the Battle of the Atlantic.

On the morning of March 17, 1943, Oberlautnant Manfred Kinzel, captain of the German submarine U-338—a.k.a Wild Donkey—ordered the cook to break out the strawberries and cream for a celebratory breakfast. Up on the surface, where Allied convoy SC-122 was churning its way from New York to Liverpool, the sea was strewn with the wreckage of Allied ships, four of them destroyed the night before by Wild Donkey’s torpedoes.

Battle of Convoys SC-122 and HX-229 March 17-19, 1943

U-boat sunk

Ship sunk by u-boat

Seventy miles away another Allied convoy, HX-229, was also counting its loses after a night of carnage: nine ships sent to the bottom, along with tens of thousands of tons of cargo and scores of sailors. It was the start of three days of terror and brinksmanship in the North Atlantic as the two Allied convoys and their naval escorts, more than 100 ships in all, found themselves beset by dozens of German submarines. It was to be the single biggest battle of the Atlantic Campaign. The outcome of World War II hung in the balance.

“Had Germany been able to cut off Britain’s supplies, that would have been it,” says Andrew Choong Han Lin, a naval historian at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England. “Churchill would have had to come to terms; there would have been no D-Day.”

Jump forward 80 years and mapping technology inconceivable in 1943 makes it possible to follow the ebb and flow of the remarkable struggle using a series of color-coded GPS points marking the sinkings of naval vessels, merchant ships, and U-boats from the first day of the war to the last.

‘Wolf packs’ rule the sea

Within hours of Britain declaring war on Germany on September 3, 1939, a German U-boat sunk the passenger liner Athena without warning off the coast of Ireland, at the cost of 117 lives. The attack was a gross violation of conventions against unrestricted submarine warfare, but soon the gloves were off, and both sides disregarded the naval gallantries they’d pledged to follow before the war.

The U-Boat war in the Atlantic through mid-1941

Total German u-boats sunk

Total casualties on German u-boats

Total Allied ships sunk by u-boats

Total casualties on Allied ships

Nobody was better prepared for submarine warfare than the German Navy. “They were right at the top of their game,” says the National Maritime Museum’s Choong Hai Lin. “They’d been practicing and honing their U-boat skills for years. Britain, on the other hand, seemed to have forgotten all the hard lessons they’d learned about anti-submarine warfare during World War I.“

The result at first was a tragic mismatch, especially after the fall of France in 1940 gave German submarines access to ports on the Atlantic. This was the start of what U-boat crews came to call the Happy Time, when submarine “wolf packs” could rove the seas with near impunity. Between July and October 1940, German U-boats sank 282 Allied ships—nearly 1.5 million tons of merchant shipping. By the following April, however, Happy Time was over. The Royal Navy had learned its lesson. The swashbuckling U-boat commanders who’d enjoyed rock-star status in the German press were dead. The Battle for the Atlantic settled into a grim and deadly struggle.

U-boats swarm U.S. coast

America entered the war in December 1941 and within weeks German U-boats were patrolling the Eastern Seaboard of the U.S. Among the first was U-123, whose 28-year-old commander sailed up to New York harbor in January 1942. Surfacing at night to admire the glow of the Manhattan skyline and the lights of Coney Island, the German submariners were incredulous that a country at war would leave its coastline so brightly illuminated. The skyglow provided a perfect backdrop for targeting ships—and the U-boats made good use of it, turning the East Coast into one long shooting gallery.

The U-Boat war in the Atlantic end of 1941 through 1942

Total German u-boats sunk

Total casualties on German u-boats

Total Allied ships sunk by u-boats

Total casualties on Allied ships

“I remember Cape Hatteras, where ships going to and from New York were steaming with full lighting,” recalled submariner Horst van Schroeter, who would later command U-123. “We cruised slowly and observed them passing. There’s one . . . no, it’s too small. He doesn’t make it into the frying pan. There . . . we’ll take that one!”

It was a feeding frenzy for the shark-like submarines. Between January and August 1942—what became known as the Second Happy Time—U-boats sank more than 600 ships along the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. and in the Caribbean. But soon the U.S. Navy started making life tough for U-boats, and the wolf packs returned to prowling the North Atlantic.

The tide turns

Germany came closest to winning the Battle of the Atlantic during the harrowing month of March 1943, sinking 97 ships in 20 days and leaving a besieged Britain with a bare few weeks of food and supplies. But the U-boats’ stunning success masked bigger problems for the German Navy. Hitler never gave the submarine corps the resources it needed for long-term success, and the Allies were finally coordinating their response in combatting the U-boat menace. Development of long-range versions of the B-24 Liberator bomber made it possible to give crucial air support to convoys all the way across the Atlantic, and American shipyards were turning out Liberty Ships far faster than German U-boats could sink them. Allied radar technology and tactics had advanced as well.

The U-Boat war in the Atlantic 1942 to the end

Total German u-boats sunk

Total casualties on German u-boats

Total Allied ships sunk by u-boats

Total casualties on Allied ships

For Germany, the Battle for the Atlantic was no longer winnable. By May 1943, sinkings of Allied ships dropped dramatically, while sinkings of U-boats soared—and would continue to do so for the remainder of the war. Among the casualties was Wild Donkey, lost with all hands on September 20, 1943.

Read This Next

Exclusive: Wreck of fabled WWI German U-boat found off Virginia

U-111 is the last known enemy submarine wreck from WWI in waters off the eastern seaboard—and never should have been found.

Sunk vessels data from Paul Heersink.

Maps data from International Conflict Research group at ETH Zurich.